Patrick Melrose: Heroin's Anti-Hero

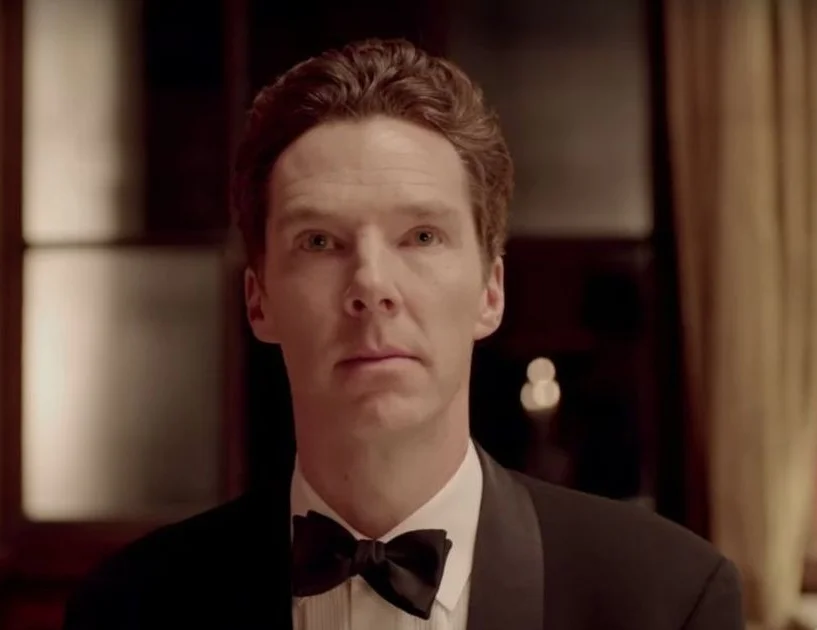

If you think that poignant storytelling around the sensitive subject of drug abuse peaked with Bojack Horseman, think again. Bojack, an entitled former Hollywood sweetheart fell from grace after being in a "very famous TV show" "back in the 90's". Struggling with the demise of his career and flashbacks from his dysfunctional childhood, he sought refuge in drug use and a steady slew of self-destructive acts. He's also a man-horse hybrid. But despite playing a dragon in The Hobbit and a posh weasel in real-life, that's where the similarities between Benedict Cumberbatch as Patrick Melrose and the aforementioned cartoon end.

You may have heard a lot about Patrick Melrose recently. Most reviews talk about the central character’s drug addiction – but the show isn’t just an incredible depiction of this; it’s the story of an anti-hero. Because despite being raped by his father since the age of five in the novels and eight in the television show, Patrick is determined to do the right thing when it comes to his own children. Adapted from a series of novels by Edward St. Aubyn, the story is semi-autobiographical in its depiction of repressive privilege and an abusive father, both of which caused so much trauma, the writer sought refuge in the mist of drug addiction: the height of Edward's addiction saw him spending $5,000 a week.

The show, punctuated at the beginning and the end of with a death of a parent, was perhaps symbolic of the two anchors that kept Patrick using. The sexual abuse that his father, chillingly portrayed by Hugo Weaving, subjected him to was an abject evil, but that his mother, played by the brilliant Jennifer Jason Leigh, was aware of her son’s continued trauma by the hands of her husband was the ultimate betrayal: his mother’s belief that ‘it’ just wasn’t talked about in those days contrasted against his firm belief that nobody should ever do ‘that’ to anyone else. Long-clasped generational beliefs of propriety weighed against the young, helpless victim of that conservatism.

In contrast to his mother, Holliday Grainger’s character, Bridget Watson Scott, puts on a great performance as the beautiful young girl who wants all the material wealth of life under the patriarchy, like a 1970's version of Katie Price. Bridget covets Patrick's father's big house and impressive grounds, but her rejection of its stuffy bigotry sees her fleeing after a disastrous dinner party. After the friend she arranged to meet fails to pick her up roadside, she walks back to the house dejected, with her suitcase. Patrick’s mother who is drunk in a car outside the house, probably considering doing the very same thing, respectfully acknowledges Bridget’s escape attempt. She gets it. She just never managed it – conformity was an anchor to an unhappy, violently abusive marriage.

However, after Bridget marries into the upper tier of society and finds out her husband has been cheating on her, she packs up a tired car with her belongings and children and this time successfully flees a repressive party scene with a triumphant smile.

The show is full of these mirror images that depict the contrasts within human nature and the outcomes for those who are bold enough to tread the paths less well-travelled, anti-heroes and heroines alike.